Sacred Connections Scotland

The Mystery of the Mother Church

Barry Dunford

Sprinkled across the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, often in remote places, are to be found curious ancient sites of religious worship known by the gaelic name of Annat or Annait which translates as the Mother Church. These Annat sites appear to be pre-Christian and apparently relate to the worship of Anaitis, the Mother Goddess of the ancient East. In the old Hebrew-Phoenician pantheon, Anaitis or Anath was the sister of the sun god Baal or Bel who was also worshipped in the Celtic regions of the British Isles, particularly Scotland and Ireland, by the lighting of Beltane fires.

Anaitis, from whence, in all probability, is derived the gaelic term annat, was a pre-Christian female deity or goddess who was worshipped not only in Egypt but also in Palestine and Asia Minor. Along with Baal, she was one of the leading deities worshipped by the Caananites in Palestine. She was also worshipped in Anatolia and Armenia, both located in Asia Minor. On this matter, an 18th century antiquary, Jacob Bryant, provides the following information in his magnum opus, A New System, or an Analysis of Ancient Mythology: “Many places were styled An-ait. Some of these were so called from their situation; others from the worship there established. The Egyptians had many subordinate deities, which they esteemed so many emanations from their chief God.. These derivatives they called fountains, and supposed them to be derived from the Sun; whom they looked upon as the source of all things. Hence they formed Ath-El and Ath-Ain, the Athela and Athena of the Greeks. These were two titles appropriated to the same personage, Divine Wisdom.. As Divine Wisdom was sometimes expressed Ath-Ain, so, at other times, the terms were reversed, and the Deity constituted called An-Ait. Temples to this goddess occur at Ecbatana in Media: also in Mesopotamia, Persis, Armenia, and Cappadocia; where the rites of fire were particularly observed. She was not unknown among the ancient Canaanites; for a temple called Beth-Anath is mentioned in the book of Joshua.”

This is supported by Edward Kenealy in The Book of God: the Apocalypse of Adam=Oannes (c1870) who comments on “.. the radical Ain, a pure Virgin, a Fountain; a name also for the Holy Spirit. Thus Aenon near the fords of Jordan, meant Fountain of the Sun: hence John baptized in it, or immersed in the Holy Spirit which was the Fountain or feminine counterpart of the Sun, namely the Moon, John iii. 23. Ath-Ain became Athena or God’s Fountain. At other times the name was reversed, and became An-Ait; a goddess worshipped throughout Asia: and by the Hebrew tribe of Naphthali, Josh. xix. 38, at Beth Anath, or the House of An-Ait. From this place they had their name Beth Ani.” Interestingly, in the Gospel texts, Mary Magdalene is identified as “Mary of Bethany”.

Writing about the Scottish Annats, Alexander Forbes in his Place-Names of Skye (1923) comments: “Many of the ‘Annats’ are claimed-and it is believed correctly-as pre-Christian.. The learned Rev. Dr. Macqueen, of Skye, also claimed the ‘Annats’ as pre-Christian, and maintained the Gaelic meaning as ‘The Water Place’.. This worship, as is generally known, came from the East, and was there among the Phoenicians, who worshipped Baal and other gods.”

In The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland (1926) Professor William J. Watson, a gaelic scholar, remarks: “.. our Annats are numerous.. They are often in places that are now, and must always have been, rather remote and out of the way. It is very rarely indeed that an Annat can be associated with any particular saint, nor have I met any traditions connected with them. But wherever there is an Annat there are traces of an ancient chapel or cemetery, or both; very often, too, the Annat adjoins a fine well or clear stream.” Professor Watson goes on to list a number of Annat sites in Scotland and remarks: “On the north side of Loch Tay, opposite Ardeonaig, is Baile na h-Annaid.. Another Baile na h-Annaide is in Glen Lyon, below Bridge of Balgie; here too there is an ancient burial-place. On the north side of Loch Rannoch, near the east end, there are an Annaid and Allt na h-Annaide..” Professor Watson continues: “In the Isles there are na h-Annaidean, ‘the Annats,’ at Shader, Barvas, Lewis. In na h-Eileanan Sianta, the Shiant Isles, i.e. ‘the holy isles,’ there is an Annaid, and another in the Isle of Killegray in the Sound of Harris, west of which is Pabbay, ‘priest isle.’ In Skye there are Clach na h-Annaide, ‘stone of the Annat,’ and Tobar na h-Annaide, ‘well of the Annat,’ at Kilbride on Loch Slapin. Another Annaid is some miles north of Dunvegan at the junction of the Bay River with a small burn, described by Boswell in connection with Dr. Johnson’s Tour. The enclosure contained about two acres and apparently had been used as a place of burial. The remains of what was probably a chapel were held by the minister, Mr. MacQueen, to have been a temple of Anaitis.”

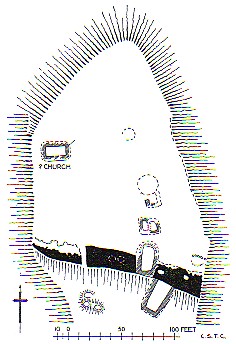

Temple of Anaitis ground plan (1921)

In her book on Hebridean folklore, The Inner Hebrides and their Legends (1964), Otta F. Swire says: “.. the Temple of Anaitis can still be found and there is a tradition that this once great temple was the centre of the ancient pagan faith of Skye..” It is interesting to note the close proximity of this ancient Temple of Anaitis, near Dunvegan on the Isle of Skye, to an Isle about five miles distant in Dunvegan Bay, called Eilean Isa (Island of Jesus) which may have been named after the presence there of Isa (Jesus) Himself. If this were the case then it is highly probable that Jesus would have visited what was effectively a pre-Christian Hebridean mystery school known as the Temple of Anaitis. There is a major question mark surrounding the “lost years” of Jesus and some traditions suggest Jesus did indeed visit a number of ancient mystery school temples. For example, in Egypt, India, Tibet and the Druid schools of learning in the ancient British Isles.

According to Charles Stewart, who was born at Fortingall, near Glen Lyon, during the 19th century, in his work The Gaelic Kingdom in Scotland (1880): “The chief seat of religious worship in Glen Lyon was at Balnahannait [town of the Mother Church], situated about six miles above the pass. The word Annait is of great interest, as it closely connects the Gaidhill [Gael] of Scotland with the cradle of the race in Asia.. Coming now to our own Gaelic kingdom, we find places called Annaits spread broadcast over the whole of it, and associated by invariable tradition with the ancient worship.” In fact, in remote Glen Lyon, the longest glen in Scotland, are to be found two gaelic Annait placenames which suggests a strong past connection with the ancient Mother Church. Alexander Stewart in A Highland Parish or the History of Fortingall (1928) remarks: “On Roromore farm [Glen Lyon] we meet the site of another of the Fingalian towers; and at Balnahanait, the farm to the west of it, there was at one time a church and a churchyard.” And in The Book of Garth and Fortingall (1888) the author Duncan Campbell comments on “Achnahanait” (field of the Mother Church) in the upper reaches of Glen Lyon, saying: “The ‘annait’ or relic chapel which was once here was surrounded by a buriel-ground of rather large dimensions, the walls of which are still very distinct. It is in a district where there never could have been a resident farming population needing such a God’s acre.. Who were then the people that used the ‘annait’?” Who indeed?

Achnahanait (field of the Mother Church) Glen Lyon

Is it conceivable that Jesus might also have visited the sacred annat sites in Glen Lyon? Glen Lyon was originally known by the gaelic name Glen Fasach, the ‘desert glen’. To have named a Scottish glen thus suggests it was a major centre of spiritual retreat, for the early Celtic monks modelled their mode of worship on the anchorite tradition of the Desert Fathers of the Middle East. Hence, a number of places of anchorite worship throughout Scotland were given the appellation diseart or dysart. In The Story of Iona (1909) by the Rev. E. C. Trenholme, the author remarks: “The word ‘disert’ is unknown in present-day Gaelic, but it was a common old Irish term when the Celtic Church flourished in Iona. Irish monasteries often had a disert near by, consisting of one or more hermits’ cells. The Iona disert seems to have been for a solitary anchorite.” Furthermore, there would appear to have been a major pilgrimage route, coming from Iona and the West of Scotland, which passed through Glen Orchy (formerly called Dysart) into Glen Lyon, Perthshire. Within this Glen, on the north side of Loch Lyon, is to be found a mountain called ‘Beinn-Mhanach’ which is Gaelic for ‘Ben of the Monks’. In The Book of Garth and Fortingall (1888) the author, Duncan Campbell, a former school teacher at Fortingall, comments: “Who, then, were the monks that gave its name to this ben? .. This region would truly have been ‘a desert’ for monks seeking seclusion from the world.”

Annait burn, Glen Lyon

It appears that no Celtic saints have been directly associated with the ancient annat sites of worship in Scotland, and later Ireland, suggesting that they were founded at least prior to 400 A. D., the approximate recorded commencement date of the era of the Celtic missionary saints. Yet these sites quite clearly represented what was considered by the Celtic Culdee monks to be the Mother Church. In the light of the foregoing research, it seems likely this parent church may have been of pre-Christian origin with connections to the Middle East and Asia Minor. It may be that the ‘mother’ church was established in order to conceive the daughter ‘Christian’ church. Clearly, there must have been a continuity with the Celtic Christian ‘daughter’ church because the annats were regarded as specific sites attributed to the ‘mother’ church long before the era of the Celtic saints. As St. Augustine observed: “for the thing itself which is now called the Christian religion, really was known to the ancients, nor was wanting at any time from the beginning of the human race, until the time when Christ came in the flesh, whence the true religion, which had previously existed, began to be called Christian.”

It would appear that the roots of Celtic Christianity, the Johannine Celtic Church of Christ, derived from a pre-Christian pagan tradition based on a mother goddess nature worship.