Sacred Connections Scotland

Were Jesus & Mary Magdalene on the Isle of Iona?

Barry Dunford

The Scottish literary writer, William Sharp (using the pseudonym Fiona MacLeod) in his essay Iona (1900) refers to “the old prophecy that Christ shall come again upon Iona.” This presupposes that Christ had already visited Iona according to an ancient oral tradition. Curiously, just 80 miles due north of Iona is to be found another small Hebridean island, located in Dunvegan Bay, off the west coast of the Scottish Isle of Skye. It is called Eilean Isa (currently spelt Isay) which translates from the gaelic as the “Island of Jesus”. Isa is the Middle Eastern arabic name for Jesus, whereas His name in gaelic is Iosa. So why do we find the appellation of this island with the arabic spelling rather than the gaelic?

The Scottish literary writer, William Sharp (using the pseudonym Fiona MacLeod) in his essay Iona (1900) refers to “the old prophecy that Christ shall come again upon Iona.” This presupposes that Christ had already visited Iona according to an ancient oral tradition. Curiously, just 80 miles due north of Iona is to be found another small Hebridean island, located in Dunvegan Bay, off the west coast of the Scottish Isle of Skye. It is called Eilean Isa (currently spelt Isay) which translates from the gaelic as the “Island of Jesus”. Isa is the Middle Eastern arabic name for Jesus, whereas His name in gaelic is Iosa. So why do we find the appellation of this island with the arabic spelling rather than the gaelic?

Interestingly, there are no religious sites on Eilean Isa or anything to suggest that it’s name was conceived from a religious dedication. During the early centuries A. D. a placename was often given to record the actual presence and sanctification of a specific place by the early Celtic Christian monastic saints who were seen as holy men and women. So it could be conjectured that the “Island of Jesus” was so named as a result of it being sanctified by the presence of Jesus Himself.

While visiting the Scottish Hebridean Islands in 1895, Henry Jenner, a former keeper of the manuscripts department at the British Museum in London, came across an intriguing oral tradition. In an article published in The Western Morning News in 1933, Jenner wrote “I was staying on South Uist, in the Catholic part of the outer Hebrides, and found there a whole set of legends of the wanderings of the Holy Mother and Son in those Islands.” Taking the foregoing associative elements into account the idea that Jesus (Isa) may actually have visited Iona may not be as far fetched as might at first appear to be the case.

Furthermore, according to Christine Hartley, in her classic work The Western Mystery Tradition (1968): “There is a legend too that Mary Magdalene lies buried in Iona.” Writing about Mary Magdalene’s legendary association with Scotland, Hartley further says, “Wandering the hills of Scotland, she came to Knoydart.” Knoydart is a peninsula located on the west coast of Scotland adjacent to the Isle of Skye which, as we have seen, has a possible association with Jesus. Some ten miles or so, south of Knoydart, can be found another west coast peninsula named Moidart where, on old maps, can be seen the placename Essa Hill, which may relate to the presence of Jesus/Isa there. Pertinently, during the 1st century A. D. Jesus was known in the Egyptian Christian Coptic Church as Essa, which is the phonetic pronunciation of Isa. It is intriguing to note that legends and placenames appear to link both Jesus and Mary Magdalene to the hebridean western isles and the west coast of Scotland.

It is likely that Christine Hartley’s source for this intriguing legend was the Scottish writer William Sharp who, in his essay on Iona, remarks: “A Tiree man, whom I met some time ago on the boat that was taking us both to the west, told me there’s a story that Mary Magdalene lies in a cave in Iona.. Perhaps an islesman had heard a strange legend about Mary Magdalene.. In Mingulay, one of the south isles of the Hebrides, in South Uist, and in Iona, I have heard a practically identical tale told with striking variations.” This would suggest there was an oral tradition current among the western isles of Scotland which placed Mary Magdalene there. Could there be some truth in this? Professor Hugh Montgomery in his treatise The God-Kings of Europe: The Descendants of Jesus traced through the Odonic and Davidic Dynasties (2006) provides the interesting information, “John Martinus was believed in the early Christian Period to be the last son of Jesus by Mary Magdalene. In some versions he was born on Iona.” Curiously, as Christine Hartley has pointed out, the holy isle of Iona was also known as the Isle of John. Could this relate to the presence of the child of Christ, John Martinus, on Iona?

The Rev. J. F. S. Gordon in his book Iona, published in 1885, comments on “Cladh-an-Diseart, ‘Burial-ground of the Highest God’ called sometimes Cladh-Iain, ‘John’s burial-ground’. It is situated some distance to the north-east of the Cathedral, in the low ground towards the water-edge, and near it on the south is Port-an-Diseart, ‘Port of the Highest God’.” It would appear this John association with Iona was of some spiritual significance. Another possibly pertinent gaelic placename is noted by the Rev. Edward C. Trenholme: “Eilean Maolmhartainn (Maelmartin’s Island) is near the south-west corner of Iona. Maelmartin (Devotee or Servant of Martin) may have been one of the ancient Celtic monks of Iona.” (The Story of Iona, 1909)

(St.) John’s Cross, Iona

On the tombstone of Anna MacLean, the last Prioress of the Nunnery on Iona, who died in 1543, is an effigy of a woman and child with an inscribed dedication to “St. Maria”. The presumption would be that this relates to Mary, the Mother of Jesus and the Christ child. However, this woman is portrayed with long hair and is flanked by twin towers, both medieval symbols to denote St. Mary Magdalene. Margaret Starbird refers to “the lore of the Mary called Magdalen, who dried the feet of Jesus with her [long] hair and whose epithet means ‘tower’ in Hebrew.” (The Woman with the Alabastar Jar, 1993) Is it possible that this tombstone actually depicts Mary Magdalene with the child of Christ, John Martinus, allegedly born on the holy isle of Iona? If so, this would suggest that Anna MacLean knew about this legend.

Anna MacLean’s tombstone

There is also an interesting early Martinus connection with Arles in celtic Gaul (now France), where a Christian mission was established by St. Trophimus, a disciple of Jesus. Tradition says that St. Trophimus travelled to Gaul with Mary Magdalene and other disciples of Jesus. He became the first of a succession of bishops of Arles holding the office from 60-80 AD. Interestingly, from 170-180 A. D. the name of the then Bishop of Arles was Martinus. Barely a century and a half later we find another Bishop of Arles, named Martinus II (316-330 A. D), which may suggest some kind of hereditary descent. Could this imply a family lineage descended from John Martinus, an alleged son of Jesus and Mary Magdalene? There is a strong tradition linking Mary Magdalene with ancient Gaul (France) and it is not impossible that a son of hers, and perhaps some of his descendants, might also have lived there.

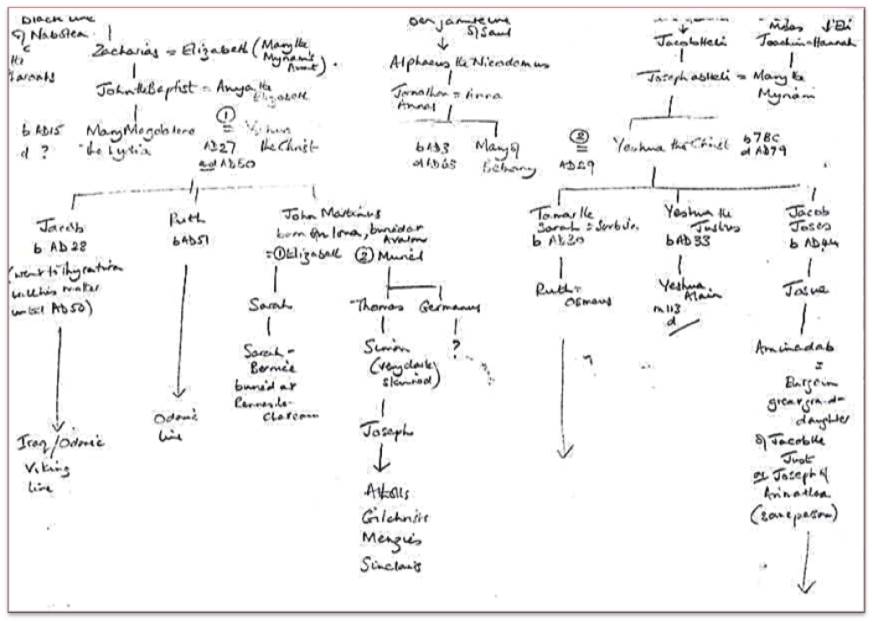

Genealogy chart showing the Jesus and John Martinus connection with Iona (courtesy of Margaret Tottle-Smith, part of her extensive historical research)

Later, we find St. Martinus of Tours (316-397 A. D), whose sister, Conessa, was the mother of St. Patrick, the Patron Saint of Ireland. Also, it is recorded that in 314 A. D three British bishops attended the Council of Arles, which not only reveals the significance of the British Christian church at that time, but also the continued importance of the apostolic succession at Arles in France.

Rather curiously, a very old tradition which appears to have originated in the Scottish Highlands and Islands refers to a St. Bride as being the “foster-mother of Christ”. She is also called “Mary of the Gael”. So clearly St. Bride in the Hebridean mythos was named Mary. However, why should she have been given the unusual appellation of “foster-mother of Christ”, particularly when it is generally believed that the Virgin Mary, the actual mother of Christ, survived her son Jesus (Isa) after his resurrection and ascension. Could the gaelic word for “foster mother” have another connotation in this particular instance? One meaning for the gaelic name Muime (foster mother) is given as “the one who gave milk” which could equally apply to a natural mother. Like the Middle Eastern Hebrew and Aramaic languages, a single gaelic word can have several meanings which would have been differentiated by the use of certain nuances. In this case could it be that “Muime Chriosta” (foster-mother of Christ) might imply the natural mother of the child of Christ rather than the foster-mother of the Christ child; particularly when the latter does not appear to make literal sense?

Mary Magdalene, Arezzo Cathedral

Surely the key to the root of this matter must lie with a specific Mary being a holy (Saint) Bride, who is also identified as being directly associated with Christ Jesus? The term Bride has a clear definition of relating to a state of marriage or marital union. So is this old Hebridean mythos indicating that Jesus and Mary Magdalene may have been married? Remarkably, in a fresco painting in Arezzo Cathedral, Italy, by Piero della Francesca (1416-92), Mary Magdalene appears to be portrayed as being pregnant, as she is also depicted in the stained glass window in Kilmore Church, Dervaig, on the Scottish Isle of Mull, approximately twenty miles from Iona.

In a West Highland incantation from the Carmina Gadelica (vol. I) occur the intriguing lines:

It was Bride the fair who went on her knee, It is the King of Glory who is in her lap. Christ the Priest above us.

Could the phrase referring to “Bride the fair who went on her knee” be indicative of Mary Magdalene (Mary of Bethany) anointing the feet of Jesus? Throughout the Hebridean western isles in particular, and the mainland of Scotland in general, there are many religious sites dedicated to St. Bride (not to be confused with the later St. Bridget of Kildare, Ireland, whose mother’s name was Brotessa). However, there are apparently no religious dedications to Mary Magdalene throughout the Hebrides and the western seaboard of Scotland. As James Murray MacKinlay notes, “There does not seem to have been any place of worship in her honour among the Hebrides, or along our western seaboard.” Why? This is rather unusual when other leading personalities around Jesus, as well as Christ Himself, are venerated in numerous chapels and churches throughout this region of Scotland. There was certainly no antagonism towards Mary Magdalene in the early gaelic christian church. Could the simple explanation for this omission be due to the fact that the gaelic people of the Hebrides and the west highlands of Scotland knew of Mary Magdalene as the Holy (Saint) Bride of Christ? How else can one account for this curious anomaly?

Bearing in mind the claim, found in early Christian Gnostic texts, that Mary Magdalene was a constant companion of Jesus, and also information which suggests that Jesus may have visited the western isles of Scotland; it would be perfectly conceivable that Mary Magdalene could also have visited the remote western isles of Scotland, hence the oral tradition there relating to a specific Holy (Saint) Bride, known as “Mary of the Gael”, who was also identified as the “foster-mother of Christ”.

Furthermore, as already mentioned, Christine Hartley refers to a specific legend that Mary Magdalene visited Iona and the Western Highlands of Scotland. Interestingly, in the Hebridean mythos Christ is called “the Shepherd of the flocks”, while St. Bride is referred to as “the Shepherdess of the flocks”. (vide Carmina Gadelica). A similar relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene is implied in the early Christian gnostic texts. The authors, Claire Nahmad and Margaret Bailey, provide the interesting comment: “We believe that in spirit, Mary Magdalene.. became one with Brigid, as she always truly was in essence, entering the British mysteries as their queen and goddess.. Brigid being that feminine essence of the Christ Light anchored in Britain but until this moment without the use of a human vehicle perfected to the point where such a sublime goddess-consciousness could become one with and shine unhindered through a single human soul. When Joseph’s staff burst into bloom on Weary All Hill, the heart of the mystic forces in Britain opened to receive the new baptism of light, and Mary became on Earth what she had always been in Heaven: one with Brigid and one with the divine rose, the fire-flower of love, which dwells at the heart of Britain, the Mystic Isle, the Grail of the world.” (The Secret Teachings of Mary Magdalene)

Regarding the Jesus/Isa connection and a possible “Holy Bloodline” in Scotland, the following information may be pertinent. It is found in Origins of Pictish Symbolism (1893) by the Earl of Southesk K. T. who quotes a letter he received from the Rev. John G. Michie of Dinnet in Aberdeenshire. The Rev. Michie states: “In regard to the name Gil-iosa, I have to bring under your notice a fact that was to me quite of the nature of an important discovery. A few days ago, when engaged in a search over the oldest church records of the parish of Kindrochit-now Braemar-I was surprised to find that one of the commonest surnames I met with was this same Giliosa, with Mc prefixed, written in very clear and unmistakable letters.. It is curious that it is only in the Braemar portion of the united parishes that I have found this surname, i. e. in the most remote, and at that time the most unfrequented, locality in Scotland, which presumably retained unchanged the most ancient surnames of perhaps a wide extent of country.”

Although gil or gille is often translated as servant in gaelic, there are various nuances in gaelic as there are in the Aramaic and Hebrew languages. In the old gaelic tradition the son of the father was often seen as serving his father, so that gil can also imply genealogical descent. Essentially, Giliosa could mean ‘son or descendant of Jesus’, and McGiliosa could indicate a son of the son of Jesus, thereby suggesting a genealogical Christic lineage. Eugene O’Growney, an Irish gaelic researcher, writing in The Irish Ecclesiastical Record (1898, vol. III), says: “The name Iosa, Jesus, gave Maol-Iosa and Giolla-Iosa, both of frequent occurrence in the old annals.. From the Gil- form comes ‘descendant of Jesus’ in the various forms MacAleese, Maclise, McLeish, Gilleece, Gillies.” The Rev. John G. Michie remarks: “Gile or Gille has often the same meaning as Mc = Mac, and naturally so, the son being often the truest follower.” He also says: “The names Gill-Iosa (Gellasius, Gillies), and Mal-Iosa (Malise) existed both in Scotland and Ireland. In the West of Scotland Iosa is pronounced as Eesa, but in the North more as Eusa (Fr. Eu).” (Quoted by The Earl of Southesk, Origins of Pictish Symbolism, 1893) This clearly illustrates how the phonetic pronunciation of a word can be spelt differently according to how a word/sound is perceived in the written language.

In his work Celtic Gleanings; or Notices of the History and Literature of the Scottish Gael (1857), the Rev. Thomas M’Lauchlan makes an interesting observation: “Reference has already been made to the great northern confederation of the Clan Chattan. It has been supposed by some that these are a branch of a great German tribe-the Catti; by others that they have derived their name from their clan badge, the mountain cat. There is little, however, to encourage the belief that either of these accounts of the origin of the name ‘Chattan’ is correct; while there is much reason to believe, that, as in other cases specified, the name is ecclesiastical, and that the clan is in reality the clan of St Cattan, a well-known Scottish saint. The name is found in other connections, as in ‘Kilchattan,’ a church in Argyllshire, and ‘Ardchattan,’ a district and parish in the same county. One of the branches of the confederation-the Macphersons-acknowledge as their ancestor Dughall Dall M’Gilleachatain. This ‘Gilleachatan,’ is just ‘The Servant of St Cattan’; and, if the name be derived from him, it is decidedly ecclesiastical. In the Gaelic MS. of 1469, found in the Edinburgh Advocates’ Library, and printed in the Transactions of the Iona Club, there is a genealogical tree of this tribe given, beginning with ‘genelach clann an Toisich an so,’ i.e., ‘Clann Gillicatain.’ The account runs thus: ‘Uilliam agus Donaill da mhic Uilliam mhic Fherchair ic Uilliam ic Gillemitil ic Fherchair’; and so on, till it comes to ‘ic Neachtain, ic Gillicatain, o fuil Clann Gillicatain’; or, in English, having traced the tribe up to Gillicattan, the writer says, from whom descend the clan of Gillicattan. If this account be correct, and there does not seem to be any reason to doubt it, this, one of the largest and most powerful of the Highland clans, bears an ecclesiastical designation, and it is in reality the children of St Cattan.” Here we find confirmation that the gaelic name Gillicattan relates to the children and descendants of an early celtic saint or holy man who, like all the other early celtic saints, both male and female, belonged to the old British royal lineages.

In Historical Walks and Names (1927) G. M. Fraser, a Scottish librarian, relates: “In this class of name our familiar expression, ‘Gille,’ comes into play, in its proper sense, meaning a servant or disciple. It is seen in such a surname as Gildea-name of a commanding officer in Scotland before the War-Gille-Dhé, Servant of God; or in Gille-Chriosd, Servant or Disciple of Christ; MacGilchrist, Son of the Servant of Christ. In Gillespie you have Gille-easpuig, Servant of the Bishop; Gillies, Gille- Josa, Disciple of Jesus, and Maclehose, Mac-Gille-Jose, Son of the Disciple of Jesus. In Gillanders you have Gille-Andreas, Disciple of St. Andrew; in Gilmour, the ‘gille’ or Disciple of St. Mary, and so on.” Furthermore, in a work entitled In Famed Breadalbane (1938) by the Rev. William A. Gillies, the author writes: “From Gille and Iosa (Jesus) come the names Gillies and McLeish; and from the same word with Criosda (Christ) we get Gilchrist and McGilchrist.” Could these Scottish family names indicate a lineage of Christic descent in Scotland which had its roots in a union between Jesus and Mary Magdalene?

According to James King Hewison, “The name ‘Gillemartin’ appeared in a very early [Scottish] Charter.” (The Romance of Dumfries and Galloway, 1939) Could this suggest a descent from John Martinus, allegedly a son of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, as mentioned earlier? A former minister of Kenmore Church, by Loch Tay, in the central Highlands of Scotland, the Rev. William A. Gillies, records the local placename: “DALMARTAIG, DALMARTENE-The plain of Martain.. Between the terrace and the bank of the river [Tay] there is a low-lying field of nine acres, now under trees, that used to be called ‘The Elysian Fields’.” (In Famed Breadalbane, 1938). This suggests that the Eleusian mysteries were performed there. This gaelic placename could also be rendered ‘the field of Martin’. Since there appear to be no historical references to St. Martin of Tours having visited the central Highlands of Scotland, could this placename allude to the presence of John Martinus, or possibly a family descendant?

Throughout Scotland there are many placenames attributed to St. Martinus of Tours of whom there is no record of him ever visiting Scotland. As already mentioned, the usual practice was for such appellations with religious connotations to originate due to the actual presence of the saint or holy person at the said places. Although in this instance there may have been some Martin placenames which resulted from the St. Martin cultus adopted by his pupil, St. Ninian (c. 400 A. D), and his followers, there appear to be far too many for them all to be attributed in this manner.

For example, G. A. Frank Knight notes: “Martin’s name spread through Scotland to an amazing degree, through the fact that Ninian and his disciples carried the fame of this great Christian soldier far and wide. Besides the peculiarly Scottish ‘term day’ named Martinmas.. we find place names throughout the land.. In Balmaghie parish is Crossmartin, associated with his memory. Blaeu’s map of 1662 gives Martinhope as a place continguous to Unthank in Eskdale. Near Aberdour on the Fife coast, Inchmartin, anciently called Ecclesmartin, suggests the linking of his name with the district. In the same county, Strathmiglo had a collegiate church, Eglismartene, bearing Martin’s name, and Cupar had its St. Martin’s fair, though it is unlikely that these connections with the Saint of Tours date back to the time of Ninian. In the Carse of Gowrie in Perthshire we have the old parish of Inchmartin, while to the north of Perth is St. Martin’s parish, which had a St. Martin’s Acre next to the churchyard. In Forfarshire the parish of Strathmartin to the north of Dundee, and a sculptured slab bearing a dragon symbol locally called St. Martin’s Stone, keep his name in memory. At Logiepert in the same shire were St. Martin’s Church, St. Martin’s Well, and St. Martin’s Den, a hollow in the neighbourhood.. a pool in the North Esk is known as Linn Martin. Formartin, the section of Aberdeenshire between the Ythan and the Don, means ‘Martin’s Land’.. “The parish of Cullicudden was dedicated to St. Martin, and in Gaelic bore the name ‘Sgire Mhartuinn.’ At St. Martin’s Farm are the remains of the foundations of a church and burying-ground called Kilmartin. Achmartin is a local name at Balblair near the Cromarty Firth, and St. Martin’s Fair used to be held in the parish on the eve of Martinmas. Still further north, in Sutherlandshire, between Ceancoille and Cnubeg in Strathnaver, is Tobair-Claish-Mhartein, a well famed for health-imparting virtues, while close beside it is a very ancient burial ground where St. Martin’s Chapel probably stood. In the wall of the graveyard is a fragment of stone bearing a cross of early Celtic pattern. At Balligil, Farr, stands Dun Mhartain, an ancient fort.. Coming down the west coast we find many traces of Martin’s influence. In the mouth of Loch Broom lies Eilean Mhartuinn, one of the Summer Isles, where there is a cross-incised stone, and which probably had a chapel associated with Martin. In the parish of Loch Carron is Dail Mhartuinn, ‘Martin’s Dale.’ In Kilmuir parish in Skye there was a chapel at Kilmartin. In North Uist there must have been a church at Balmartin, with its cluster of a township beside it. In Mull near the head of Loch-nan-Gall is an ancient church site known as Kilmartin.. In Islay his name is preserved in the township of Ballimartin. On the north side of the Crinan Canal is Kilmartin parish.. In Loch Sween is Isle Martin with a ruined chapel on the east mainland opposite. In Glen Urquhart parish, Invernesshire there is also a Kilmartin.” (Archaeological Light on the Early Christianizing of Scotland, Vol. I, 1933)

James M. Mackinlay also observes: “In the Strathmore district of Perthshire is the parish of St. Martin’s, whose name leaves no doubt as to the dedication of its ancient church. This seems to be the ‘Sanct-Martines, alias Melginche,’ referred to in charters of 1624 and 1633. In 1598 a field beside the churchyard was known as St. Martin’s Acre.. The church of Logie-Montrose in Angus owed allegiance to St. Martin, whose name is still preserved in St. Martin’s Well, and in a neighbouring hollow known as St. Martin’s Den.. A chapel bearing St. Martin’s name was situated, along with its graveyard, on a rising ground at the east end of Nungate, a suburb of Haddington, on the right bank of the Tyne. It was a dependency of the Cistercian nunnery of Haddington, founded by Countess Ada, mother of Malcolm IV, and William the Lion. The land on which it stood was granted by the Countess to Alexander St. Martine, and it was he, according to Dr. J. G. Wallace James, who probably built the chapel.” (Ancient Church Dedications in Scotland, 1914) One might wonder who were the antecedents of Alexander St. Martine? Likewise, what were the origins of the Scottish Clan MacMartin known to date at least as far back as the Middle Ages. In the account Description of the Western Isles of Scotland, first published in 1703, and ironically written by Martin Martin, when describing the western Isle of Eigg, the author observes: “There is a heap of stones called Martin Dessil-i.e., a Place consecrated to the saint of that Name-about which the Natives oblige themselves to make a Tour round Sunways. There is another heap of Stones which, they say, was consecrated to the Virgin Mary.”

It may be worth remembering the oral tradition and legends linking , Jesus, His Mother Mary and Mary Magdalene, to the western isles of Scotland. While one can understand that some chapels and Kilmartin placenames may have as their origin religious dedications to St. Martin of Tours, nevertheless such old gaelic placenames translating as St. Martin’s Acre, St. Martin’s Den, Martin’s Land, Martin’s Well, Martin’s Isle and Martin’s Dale are more likely to have arisen due to the actual presence of a holy person named Martin. As mentioned, since there is no record of St. Martin of Tours ever visiting ancient Alban (Scotland), it could be conjectured that some, at least, of these gaelic Martin placenames may relate to John Martinus, or possibly some of his descendants who would no doubt have continued the spiritual work initiated by their illustrious and holy forbears. Interestingly, Otta F. Swire, a Scottish folklorist, comments on an early medieval carved tombstone, in the style of those found on Iona, located in the old graveyard of Kilmuir on the Isle of Skye, saying: “It marks the grave of Angus Gille Martin, the first member of the Martin family to settle in Skye.” (Skye: The Island and its Legends, 1961)

There is an ancient high cross on Iona known by the gaelic name Crois Mhartuinn which translates as Martin’s Cross, not incidentally Saint Martin’s Cross. It is generally attributed as a dedication to Saint Martin of Tours. Curiously, this cross, portraying the Mother of Christ and her child, implying a possible genealogical association, was sculptured by a man named Gilchrist. Coincidence? The author’s A & E. Ritchie, in Iona Past and Present (1934) record “In the summer of 1927, Professor R. A. S. Macalister had the bottom panel on the obverse side freed from lichen, and discovered a faint inscription in Irish letters which, when translated, reads: ‘A prayer for Gilla Crist who made this cross’.”

Crois Mhartuinn (Martin’s Cross)

Is the alleged Saint Martin’s Cross on Iona referring to St. Martin of Tours or might it relate to John Martinus, particularly when one remembers the earlier reference to the intriguing St. Maria effigy inscribed on the tombstone of the last prioress of the nunnery also on Iona. Could we be touching here on some of the “secrets of the North” to which the Scottish writer William Sharp alluded? Sharp spent a considerable amount of time on Iona while investigating the traditions and legends of the western isles of Scotland.

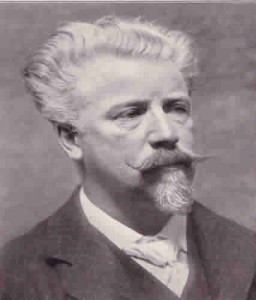

William Sharp (1855-1905)

In several of his fictional stories William Sharp places Jesus in the Scottish highlands, and in one entitled The Wayfarer he implies the presence of both Jesus and Mary Magdalene being there. Sharp writes: “Among those in the home-straths of Argyll.. a stranger came into Strath Nair, and spoke of the life eternal.. Over the slope beyond Monanair Mary Gilchrist appeared. She was walking slowly, and as though intent upon the words of her companion, who was the wayfarer.. the stranger who was with Mary Gilchrist arose. None knew him. His worn face, with its large sorrowful eyes, his long, fair hair, his white hands, were all unlike those of a man of the hills; but when he spoke it was in the sweet homely Gaelic that only those spoke who had it from the mother’s lips.. ‘Listen,’ said the wayfarer, ‘while I tell you the story of Mary Magdalene’.. Mary Gilchrist had kneeled by his side, and held his left hand in hers, weeping gently the while. A light was about her as of one glorified. It was, mayhap, the light from Him whose living words wrought a miracle there that day.. And not one there but felt how sacred and beautiful in their eyes was the redemption of the woman Mary Gilchrist, who was now to them as Mary Magdalene herself.. But in the gloaming, in the dewy gloaming of that day, Mary Gilchrist walked alone, with her child in her arms, in the Glen of the Willows. And once she heard a step behind her, and a hand touched her shoulder. ‘Mary!’ said the low, sweet voice she knew so well, ‘Mary! Mary!’ Whereupon she sank upon her knees. ‘Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God!’ broke from her lips in faint, stammering speech.” (My italics-BD)

Is William Sharp implying that Jesus (Isa) from Galilee (the land of the gael?) was of gaelic descent? If, as Hebridean oral tradition suggests, Jesus and His Mother, Mary, came to the western isles of Scotland, then presumably they would have conversed with the native people in gaelic. Was William Sharp, partly as a result of a localised oral tradition, and perhaps intuitively as well, detecting the presence of Jesus and Mary Magdalene in the highlands and islands of Scotland?

Writing about “The secret of Iona” Sharp calls the Island “This little holy land!”, and he also relates: “In spiritual geography Iona is the Mecca of the Gael.” William Sharp further remarks: “I have long had a conviction-partly an emotion of the imagination, and partly a belief insensibly deduced through a hundred avenues of knowledge and surmise-that out of Iona is again to come a Divine Word.” Out of Iona is again to come a Divine Word. Now what might this spiritual revelation imply?