Sacred Connections Scotland

The Face of Christ

Barry Dunford

The following intriguing information, which may indicate a very early Hebraic-Christian connection in the British Isles, is to be found in British History traced from Egypt and Palestine (1927) by the Rev. L.G.A. Roberts, who says, “that very early, the Gospel came by the hands of Hebrews is borne out by the finding of two medals bearing the effigies of our Lord, without a halo; one of these was unearthed at Cork, in 1812, under the foundation of one of the very first Christian monasteries ever built in Ireland; the other under the ruin of a Druidical circle at Bryn-gwin, in Anglesea [North Wales]….Antiquarians inform us that the Hebrew letter ‘Aleph’ on the obverse side to the right of the effigy of one of these, gives the date as the first year after the resurrection, the other Hebrew letters signifying Jesus, on the left: the word Messias is on the collar, and the reverse side has an inscription in Hebrew.”

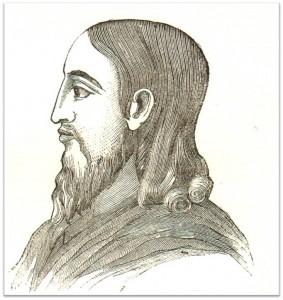

Jesus medallion found at Bryn Gwyn stone circle, Anglesey, north Wales

In his Mona Antiqua Restaurata: An Archaeological Discourse on the Antiquities of the Isle of Anglesey, (1766, 2nd edtn) first published in 1723, the Rev. Henry Rowlands records: “Bryn-Gwyn or Brein-Gwyn, i.e. ‘the supreme or royal tribunal’; Brein or Breiniol signifying in the British, supreme or royal; and Cwyn, properly suit or action, and metaphorically court or tribunal….the composition of the name taken from British etymons, Brein and Cwyn, and its position so near the places which bear the names of all the Druidical orders, may well justify the conjecture of its having been once the supreme consistory of the Druidish administration….the word Bryn gwyn is undoubtedly applied to the great council of the nation….At the round cirque at Bryn Gwyn was taken up, the other day, a medalium of our Saviour, with the figure of his head and face on the one side, exactly answering the description given of him by Publius Lentulus; and on the reverse, a fair Hebrew superscription bearing this purport, viz. ‘This is Jesus Christ the Reconciler’….One of the seats of judgment whereon they exercised that power by acquitting or condemning, as I have before shewed, was in the Isle of Mona; that a medal of our Blessed Saviour was taken up out of the rubbish of that very mount or tribunal, where their sentences and judgments were pronounced; that seeing it was taken up in so obscure, unfrequented, and desolate a place as now it is, and I believe ever since was, none can well doubt of its being true and genuine, the circumstances of thing and place considered; that bearing on it a Christian inscription, importing, ‘This is Jesus Christ the Mediator,’ it must be supposed to have been brought there by some Christian.”

Rowlands further says: “Concerning our Saviour’s Medal….found among the rubbish of an old circular entrenchment, called Bryn-Gwyn, in the middle of the township of Tre’r Dryw….that place’s being the Forum or tribunal of the ancient Druids….I had caused some figures of it to be delineated in rundles on paper, and writ the Hebrew inscription on the reverses of them with my interpretation of it; and having sent one of them to my late worthy friend, Mr. Edward Lhwyd, then at Oxford, desiring him to consult some friends there who were versed in the antiquities of that language about it, he returned me the answer he had from Dr. Crossthwait of Queen’s college, which was thus: ‘Sir, As to the brass Medal, bearing our Saviour’s image, with a Hebrew inscription; I have this to say: That I take this to be the inscription, viz. Jeschuah gibbor Meschiah havah v’Adam joked; that is, ‘Jesus is and was the mighty and great Messias, or Man-Mediator or Reconciler’….Theseus Ambrosius says he saw a brass Medal of our Saviour with the inscription mentioned above in the time of Julius II and Leo X that is about the years 1503, and 1512….Sanctus Pagninus observes in his Tract of Hebrew Names, that on the piece of the title of the cross, to this day kept at Rome (Roma siqua fides) as a sacred relic, our Saviour’s name thereon is found written ?? Teschuang, as it is on this Medal….this Medal of our blessed Saviour bears not a Jewish but a Christian inscription upon it, I then humbly conceive it may be of very ancient date, if not from the time of his being on earth.”

In an essay entitled Ancient Portraitures of our Lord, published in the Archaeological Journal (c.1873), Albert Way, Director of the Society of Antiquities, comments on the Jesus medal mentioned by the Rev. Henry Rowlands, saying: “It had been found, about 1723, at the ‘round cirque at Bryn Gwyn’ – the supreme tribunal – in Anglesey. This medal is described as of brass; this, however, might obviously designate bell-metal, especially if its surface were discoloured or decayed. We cannot marvel that the discovery, having occurred near Tre’r Dryw, with its supposed Druidical grove and megalithic monuments, was advanced in confirmation of the conjecture that the place had been the Forum or tribunal of the Druids. Edward Lhwyd, the learned custos of the Ashmolean, willingly sought aid from the most eminent Hebraists in the university to elucidate so rare a relic of antiquity, in those hazy times when erudite scholars gravely discussed the probability that Hebrew was the tongue of Noah and his family.” Way also refers to another Jesus medal “found in county Cork in 1812, and supposed to have been brought into Ireland at some early period after the introduction of the Faith. The medal had been found in digging potatoes on the site of a very ancient monastery, of the first Christian ages.”

In support of this an Irish researcher, Henry O’Brien, writes about, “Three profile likenesses of Christ, as he appeared upon earth in human form—the first is a facsimile from a brass medal, found at Brein Owyn, in the Isle of Anglesey, and published in Rowland’s ‘Mona Antiqua.’ The inscription upon it has been translated, as meaning, ‘Jesus the Mighty, this is the Christ and the man together.’ The second, likewise of brass, and found at Friar’s Walk, near Cork, is now in the possession of a Mr. Corlett – [with an] inscription upon one side, ‘The Lord Jesus’ – upon the other, ‘Christ the King came in peace, and the light from the heaven was made life’….observe here, that he does not say the word was made life, but the light was made life. The third is of silver, and the inscription means, ‘Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ—the Lord and the Man together.’ The originals of these inscriptions are all in Hebrew, and the likenesses which accompany them, although on different metals, appear almost copies one of another.”

An interesting aside regarding these Jesus’ medals is provided by Patrick Benham in his book The Avalonians (1993). Writing about Dr. John A. Goodchild (1851-1914), a researcher into the early history of Christianity in Britain, Benham says: “The other great subject that absorbed his interest at that time was gematria – the means by which every word or group of words is given a numerical value according to the sum of the numbers assigned to its component letters. Different words and phrases might have the same value, implying that they share a special power and quality transcending their more obvious meaning. The system was applicable to different alphabets (and even a function in the evolution of those alphabets in past times). In Hebrew it was more obvious as the letters are used for numerals in any case….There was one number which Goodchild held up above all others….The calculation of this number was on the Hebrew form of the name – meaning Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, Jesus of Nazareth – giving the Divine Number 1642. How the doctor arrived at his knowledge of the ‘Number of the Master’ is unclear. He put some store on the witness of the Campo di Fiori Medal, a coin-like item in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, of uncertain date, said to depict a profile of the head of Christ. His starting point may have been the fact that the Hebrew inscription on one face added up to 1325, and on the other to 317. These are the same values as those just shown for Jesus Christus + O A?AMA? [i.e. 1642].”

Charles Maitland, MD, in his book The Church in the Catacombs (1847) observes: “Sacred painting, in professing to preserve the portraits of the first founders of Christianity, proffers a strong claim upon our attention. The representations of the Saviour, which became very numerous in the fourth century, agree so remarkably with each other, that it has been supposed by many that some authentic portrait must have been preserved….Among the portraits of our Lord, pretended to have been taken during His life time, the most celebrated is that said to have been presented to Abgarus. Eusebius, translating from a Syriac manuscript found at Edessa, tells us that Abgarus (or Agbarus), king of that city, having heard of our Saviour’s miracles, conceived an earnest desire to see Him, and sent a messenger, requesting Him to take up His abode at Edessa, as a shelter from the malignity of the Jews [Judeans]. The kindness of Abgarus was acknowledged by the divine wanderer, who wrote a letter, commending the faith of Abgarus, and explaining the nature of His own mission, which forbad the proposed visit. The entire story rests upon the authority of this manuscript, there being no apostolic tradition on the subject. Eusebius wrote this about 320….The Gnostics, it is well known, had portraits of our Saviour, professing to be copies of the likeness said to have been taken by command of Pontius Pilate….Since no likenesses of our Lord were possessed by the orthodox up to the fourth century, it becomes a question of some difficulty, whence they procured the type which was almost universally received in the fifth.”

John P. Lundy provides the further interesting comment: “The Gnostics are the first we read of as having made any pictures of Christ, and as early as A.D. 150. It was by these sectaries, says M. Raoul Rochette….that little images of Christ were first fabricated, the original model or likeness of which was traced back to Pontius Pilate, who is said to have caused it to be taken from the Original. This we have from St. Irenaeus, who tells us of ‘a certain woman named Marcellina, of the sect of Carpocrates, who, to propagate the Gnostic doctrines at Rome, came from the far East, during the episcopate of Anicetus….They style themselves Gnostics. They also possess images, some of them painted, and others formed of different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at the time that Jesus lived among men. They crown these images, and set them up with the images of Plato and Pythagoras and the rest; and have other modes of honouring them after the same manner as the Gentiles.’ The mention of Anicetus fixes the date A.D. 156; and these images of Christ must have been in existence before, a possible example of which is on the title-page of this book, and which Agincourt claims to belong to the first century. It is like the story which Lampridius tells of the Emperor Alexander Severus, placing among his household gods the portraits of Christ and of Abraham, opposite to those of Orpheus and Apollonius of Tyana, and between images of the most revered kings and philosophers, paying them all a sort of divine homage.” (Monumental Christianity or the Art and Symbolism of the Primitive Church, 1876) The significance of Pontius Pilate’s involvement in the making of a portrait of Christ is intriguing. According to an apocryphal tradition in the non-canonical Gospel of Peter, Joseph of Arimathea (a relative of Jesus) was “the friend of Pilate and of the Lord”.

Regarding the Face of Christ, the Rev. W.H. Withrow says: “Jerome conjectures that there must have been something celestial in his [Jesus] countenance and look, or the apostles would not immediately have followed him; and that the effulgence and majesty of the divinity within, which shone forth even in the human countenance, could not but attract at first sight all beholders. Chrysostom and Gregory of Nyssa in the East adopted this nobler conception, as also did Ambrose and Augustine in the West….no authentic portrait of Christ was recognized by the early church; nor was any strictly uniform type adopted. Eusebius, indeed, mentions reputed portraits of Our Lord associated with those of St. Peter and St. Paul; but they were apparently objects of mere local superstition, as was also the alleged statue of Christ at Caesarea Philippi, in which he was supposed to be represented as healing the woman with the issue of blood. The earliest acknowledged images of Christ were attributed to the Gnostic heretics, and were honoured with those of Homer, Pythagoras, Orpheus, and other heroes and sages by the eclectic philosophers of Rome [and apparently Pontius Pilate]….

Jesus’ portrait in the Roman catacombs

“The oldest extant picture of the head of Christ treated separately is a profile brought from the Catacomb of Callixtus, now in the Christian Museum of the Vatican….It is in imitation of a mosaic, about life-size, and of a different type from the figure of Our Lord in composition in the frescoes and sculptures of the Catacombs. He is portrayed as of adult age, his calm, smooth brow shaded by long brown hair which is parted in the middle and falls in masses on the shoulders. The eyes are large and thoughtful, the nose long and narrow, the beard soft and flowing, and the general expression of countenance serene and mild. This became the hieratic type of many of the noblest pictures of later Italian art, and, according to the Abbé Brivati, inspired the genius of Da Vinci, Raphael, and Caracci. In the Catacomb of Sts. Nereus and Achilles the head and bust of Christ form a medallion in the centre of a vaulted ceiling. The face is of a noble and dignified expression, mingled with benevolence; but it is older in aspect, and probably of considerably later date, than that here given. Kugler, however, claims for it priority of origin. Both of these were probably of the latter part of the fourth century, and were executed not by the Christians of the purest ages of the church, but by those who had begun to walk by sight and not by faith. The primitive Christians, we have seen, had no professed portraits of Christ, but only allegorical representations of the Good Shepherd….On a terra cotta medallion, found not in the Catacombs themselves, but in the rubbish near the mouth of the cemetary of St. Agnes, is a head of Our Lord….of much superior execution. The face is of exquisite beauty, and is characterized by a sweet and tender grace of expression. But with the decline of art and the corruption of Christianity this beautiful type disappeared, and a more austere and solemn aspect was given to pictures of Christ.” (The Catacombs of Rome and their Testimony Relative to Primitive Christianity, 1895)

What is striking is the similarity between the oldest known portrait of Christ (probably 2nd century A.D.) from the catacomb of Callixtus in Rome, and the profile of Jesus on the medallion, found at the Druidic megalithic stone circle Bryn Gwyn, on Anglesey, North Wales, as mentioned above. Could this medallion, with its Hebrew inscription relating to Jesus, be of a similar early dating? If it is a later copy, who had access to the original portrait and why was it specifically used? And not with a Latin inscription as might have been expected but rather with ancient Hebraic glyphs. The 18th century antiquary, Henry Rowlands, was of the opinion that the Bryn Gwyn Jesus medallion could have been contemporary with the 1st century A.D. mission of Christ.